Understanding Bladder Cancer

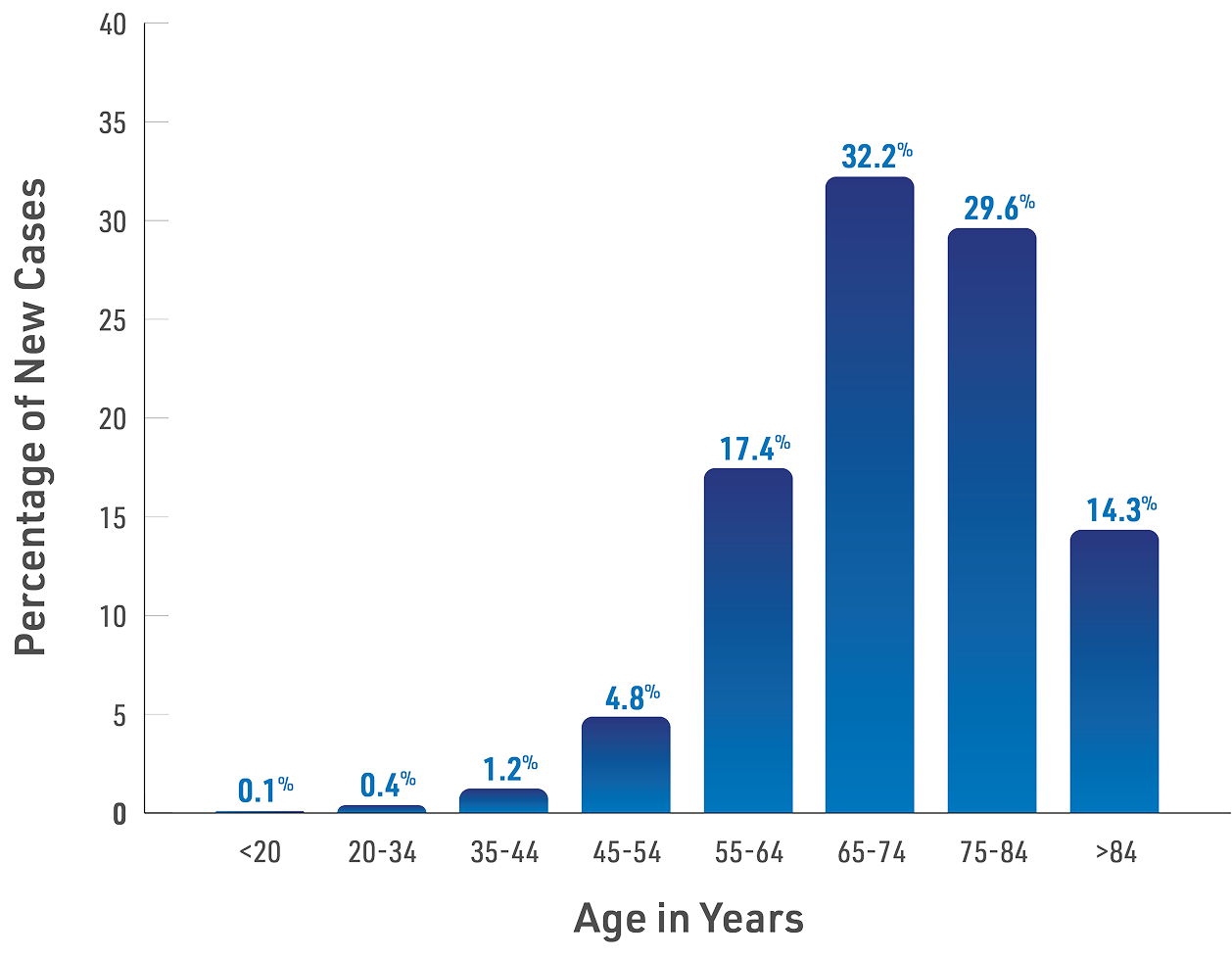

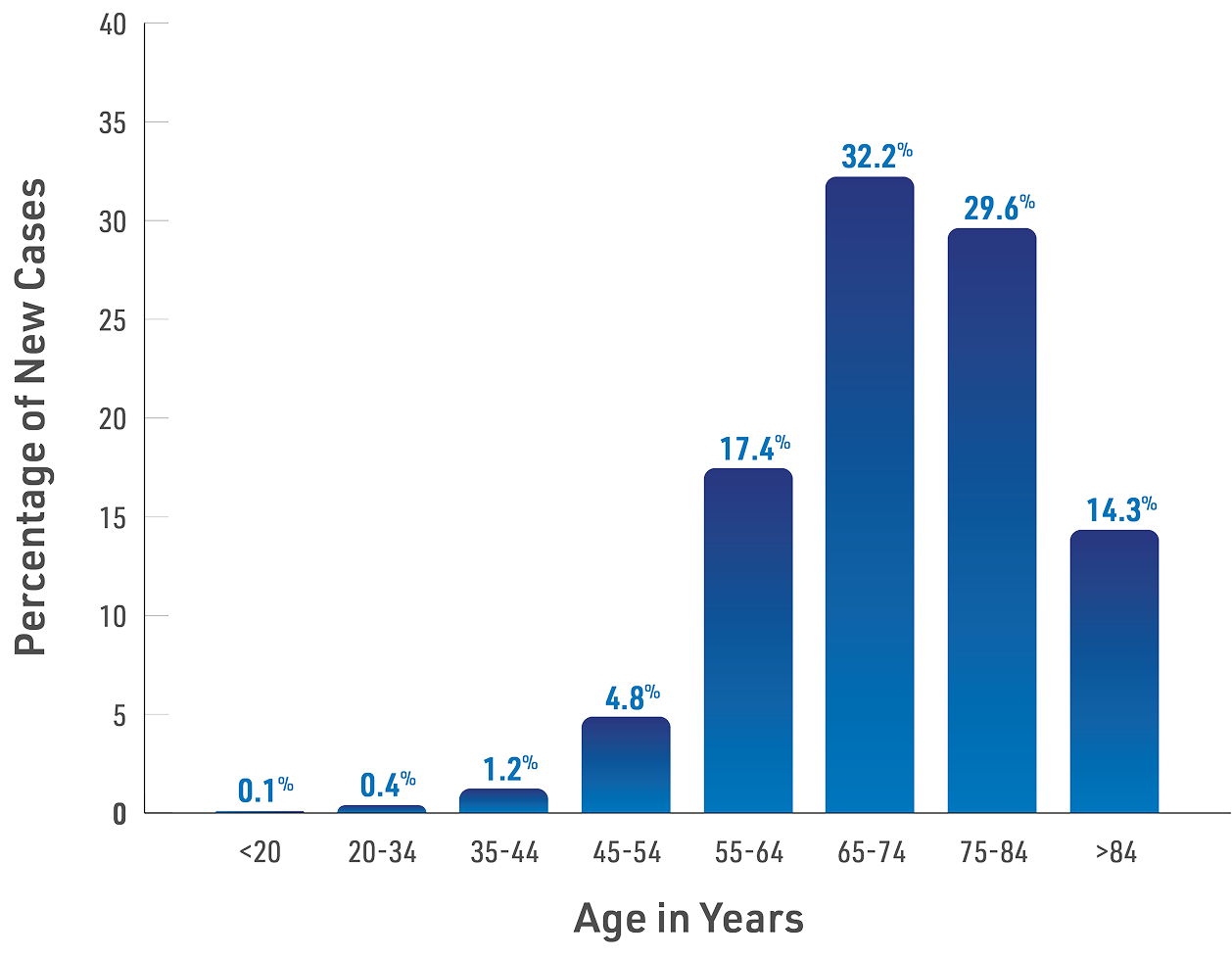

Risk factors for bladder cancer

Signs and symptoms

- Blood in urine (hematuria) is often the first sign of bladder cancer. Urine may appear pink or dark red. Sometimes the urine appears normal, but blood is detected in a urine test.

- Frequent urination

- Painful urination

- Having trouble urinating

- Lower back pain

Diagnosing bladder cancer

A urinalysis is a lab test to check for blood and other substances in your urine. Urine cytology involves examining your urine under a microscope to look for cancer cells or other abnormal cells. Urine biomarker tests may also be done along with urine cytology. These tests look for certain markers that bladder cancer cells make.

If bladder cancer is suspected, your doctor will likely perform a cystoscopy. This requires inserting a thin (flexible or rigid) tube with a camera or lens and light (cystoscope) through your urethra so the urologist can see inside your bladder. If tumors or suspicious areas are seen during the cystoscopy, your doctor may perform a biopsy. A biopsy involves removing tissue samples for examination. This procedure is usually performed in a doctor's office or surgical suite and may be referred to as a cold-cup biopsy.

TURBT is a procedure that is used to diagnose as well as treat bladder cancer, usually performed as an outpatient procedure in a hospital operating room. Patients will either be asleep (general anesthesia) or awake but numbed below the waist (regional/spinal anesthesia). Additional details on this procedure are covered under Treatment.

For diagnosis, tumor samples will be removed and sent to a pathology lab for analysis. The lab creates a pathology report and provides the information to your doctor. This report, along with other factors your doctor considers, will determine your type, stage, grade, and risk level.

Your doctor may use one or more imaging tests to get more information. Some of the more common imaging tests are CTU, MRI, and ultrasound.

- A CTU (computed tomography urogram) uses x-rays to scan the kidneys and ureters for lesions. This is important because a small percentage of patients with bladder tumors also have lesions in the upper urinary tract.

- An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) uses magnetic fields rather than x-rays to create images. It can help see if the cancer has spread beyond the bladder to nearby tissues or lymph nodes.

- An ultrasound uses sound waves to create images of organs and associated tumors. Because it is not effective for detecting small or flat tumors, it is not typically used in bladder cancer. Ultrasound is effective, however, for evaluating kidney lesions and/or ruling out urinary obstructions.

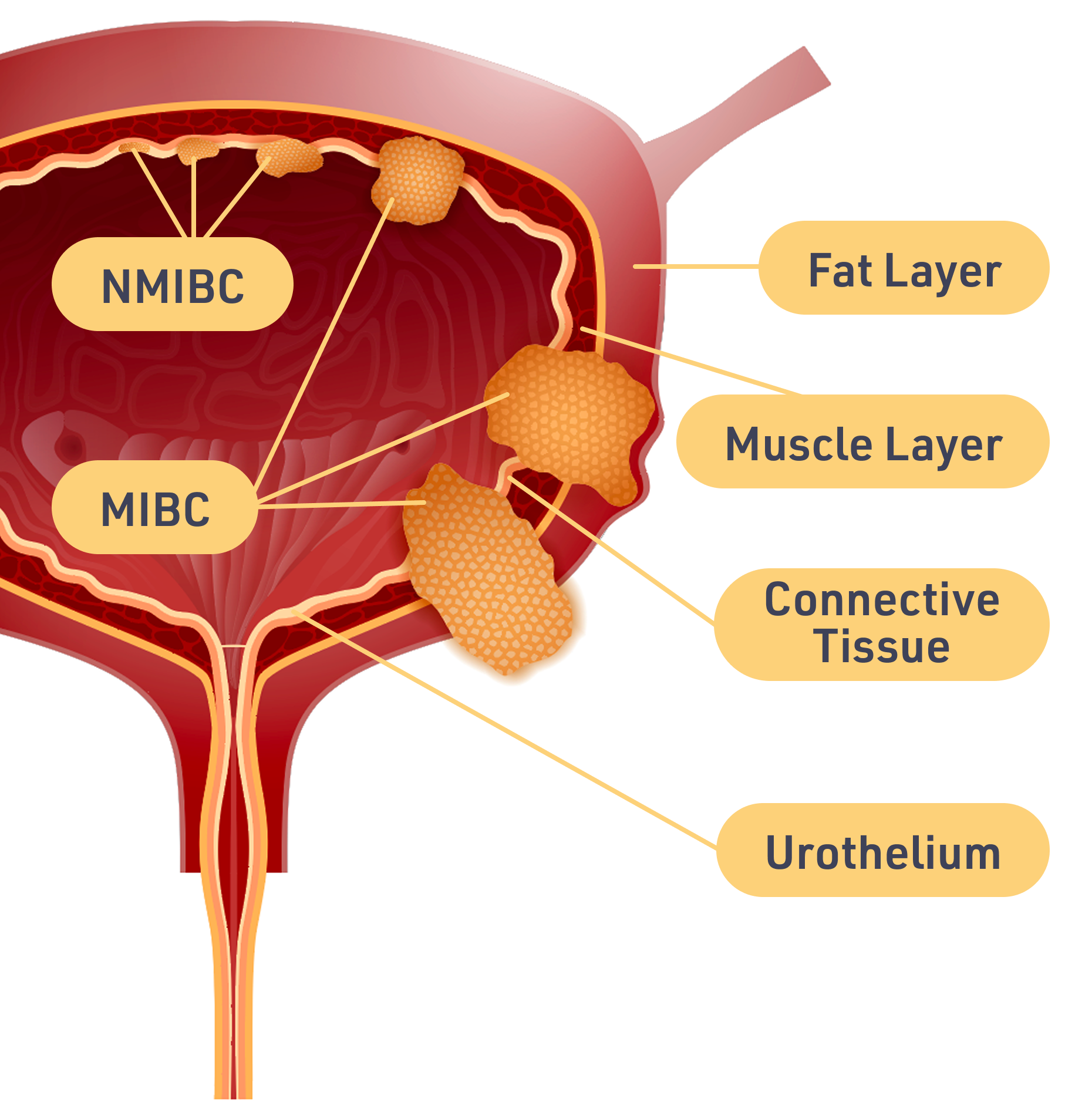

Bladder cancer categories

NMIBC is located only in the inner layer of the bladder, which is known as the urothelium. For this reason, these cancers are sometimes called urothelial. They have not reached the bladder's muscle wall.

About 75% of bladder cancers are non-muscle invasive. These cancers have a high survival rate: about 93% at 5 years. However, these cancers often return after treatment. If they do, they must be treated again.

Muscle invasive bladder cancer, or MIBC, is more serious because the cancer has grown past the lining of the bladder and into the muscle wall. These cancers are more likely to spread and are usually harder to treat.

Advanced and Metastatic Bladder Cancer

A locally advanced cancer is one that has grown outside the bladder but not spread to other parts of the body. Metastatic is a cancer that has spread to other organs. These cancers are also referred to as stage 4.

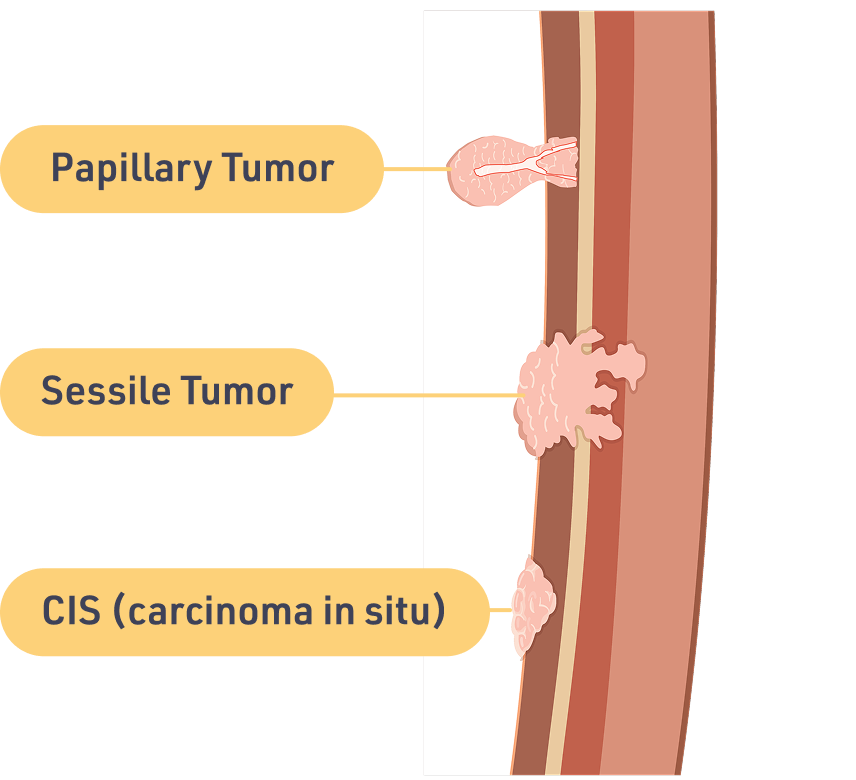

Forms of NMIBC tumors

- Papillary tumors

These grow along the bladder wall. They have small, thin arms that reach out toward the hollow center of the bladder. These tumors can be either slow growing (low-grade) or fast growing (high-grade). - Sessile tumors

Like papillary tumors, these grow along the bladder wall. But unlike papillary tumors, these are solid, flat masses. These tumors are considered fast growing (high-grade). - CIS (carcinoma in situ)

This is another type of flat tumor growing in the inner layer of the bladder. CIS tumors have not grown inward toward the hollow part of the bladder. They also have not invaded the muscle of the bladder wall. Yet, CIS is a more serious bladder cancer. It is more likely to come back after treatment or get worse. CIS tumors are classified as fast growing (high-grade).

Stages, grades, and risk levels

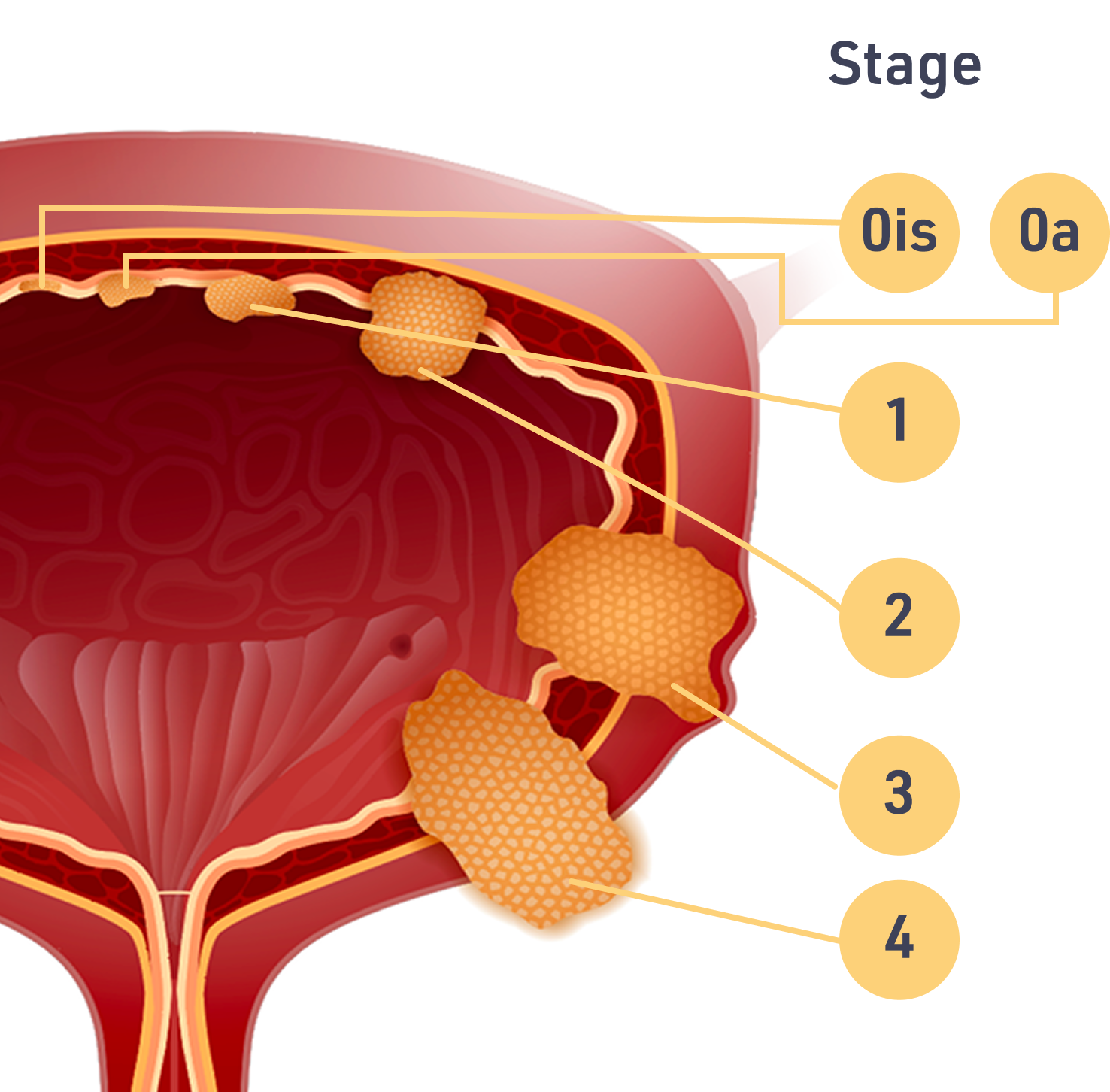

Staging Bladder Cancer

When doctors look at bladder cancer, they try to figure out how deep the cancer is and how far it has spread. This is called staging. The higher the stage, the further the tumor has grown through the layers of the bladder wall.

These are the stages doctors use:

| Stage | Description |

| 0 | Only the inner lining of the bladder is affected. The cancer is not muscle invasive. There are 2 subtypes to Stage 0: Stage 0a and Stage 0is, or CIS. |

| 1 | The cancer has grown beyond the bladder's inner lining and into the layer of connective tissue next to the lining, but it is not muscle invasive. |

| 2 | The cancer has grown beyond the bladder lining, through the connective tissue, and into the muscle wall of the bladder. At this point, the cancer has become muscle invasive. |

| 3 | The cancer has grown through the bladder wall and into the fatty layer outside the bladder. |

| 4 | The cancer has spread beyond the bladder, possibly to lymph nodes or other organs. |

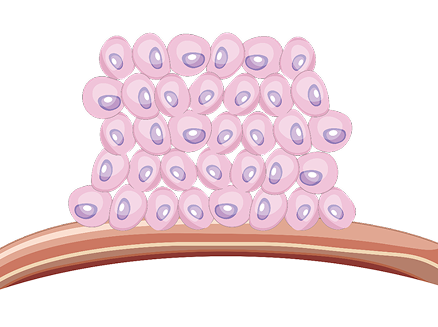

Grading Bladder Cancer

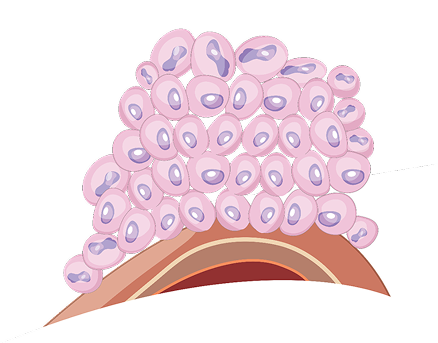

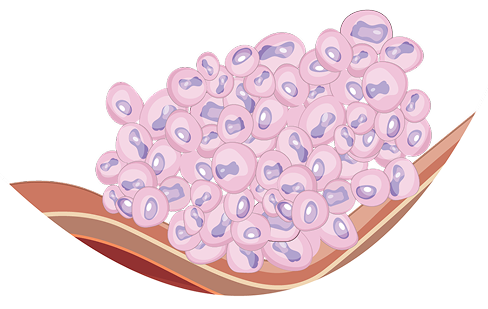

Grade measures how aggressive the cancer is. Bladder cancers are graded by how the cancer cells look under a microscope and how much they are multiplying. There are 2 grades: slow growing (low-grade or LG) and fast growing (high-grade or HG).

When normal cells reach a certain density, they stop dividing and enter a resting phase. This is not true of cancer cells.

These bladder cancer cells will likely grow and spread more slowly than fast-growing (high-grade) bladder cancer cells.

These bladder cancer cells tend to be more aggressive. They are more likely to spread into the wall of the bladder and beyond. Most invasive bladder cancers are high-grade. They tend to be more difficult to treat.

The cancer's grade is separate from its stage. Ask your doctor to tell you the grade and stage of your tumor.

Risk Levels

Treatment for NMIBC depends on how much risk there is of the cancer coming back after treatment, timing and frequency of recurrences (when the cancer comes back after it has been treated and thought to be gone), and the risk of spreading further (progression). The level of risk is determined based on several factors, including the stage, grade, size, and number of tumors that are present.

There are 3 risk levels: low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk.| Risk Level | Characteristics of the Cancer |

| Low Risk |

|

| Intermediate Risk |

|

| High Risk |

|

Small: tumor that is 3 cm or smaller in size Large: tumor that is greater than 3 cm in size Low-grade (LG): slow growing High-grade (HG): fast growing | |

There are many details that determine whether NMIBC is low risk, intermediate risk, or high risk. The table above gives you an idea of how complicated it can be.

For diagnosis, tumor samples will be removed and sent to a pathology lab for analysis. The pathology report will provide information such as the type, stage, and grade of cancer. Your doctor will use this report along with other factors to also determine your risk level.